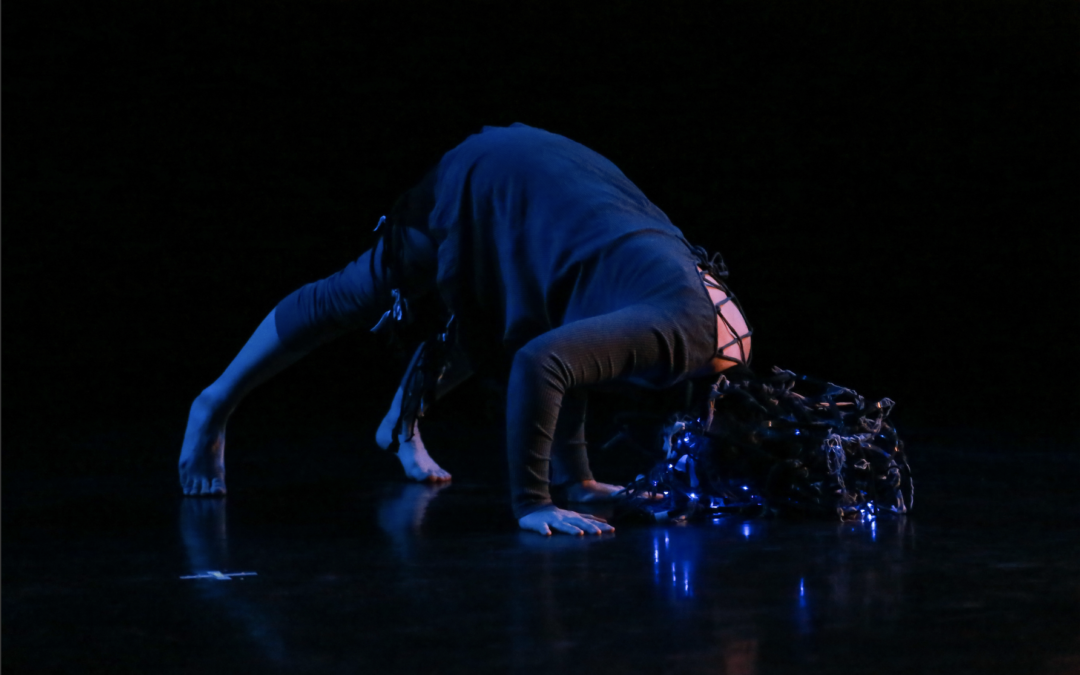

Communications Associate, Kiersten Resch, recently interviewed Karen Krolak to learn more about her work and experience as one of the 2018-2019 I-ARE Artists for The Dance Complex.

Karen is the co-founder/Artistic Director of Monkeyhouse and has been working for many years with social constructs of language and how language impacts everyone through their daily lives, specifically through moments of loss. As a performance artist, Karen takes full advantage of the community atmosphere The Dance Complex provides in the creation of their I-ARE projects.

2018-2019 I-ARE Artist DeAnna Pellecchia was also interviewed by Kiersten Resch. To see her joint interview with Karen Krolak, check the The Dance Complex website next week!

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity

Q: What is the concept of your work for the I-ARE Residency 2018-2019?

A: I am building a series of pieces related to entries in The Dictionary Of Negative Space (https://dictionaryofnegativespace.com) an ongoing project that I launched in June 2018. The Dictionary digs into the nameless ideas that exist in the aftermath of trauma and loss and I began it as part of my thesis project for my MFA in Interdisciplinary Art at Sierra Nevada College.

In the dictionary, [49] for example is a parent who outlives their child. We have a word for a child who loses their parent, but we don’t have anything that fills in that space for a parent when they lose a child and the change in their identity that happens there. Yet this is one of the most difficult losses that anyone talks about enduring.

An example of some of the more pedestrian things that are in it is [1]: the last place you see a person alive, which again feels like something we should have a word for yet there is nothing in our language that fills that space. Because we don’t fill it in, we often don’t notice it, yet people will discuss having extremely emotional responses to those spaces.

Q: What drove you to work with this topic?

A: In August 2012, my mother, father and older brother were killed in a car accident in upstate New York. At the time, my husband, our dog and I were in the middle of a move and living on Nicole Harris’ couch.

About a month later, Springstep called to announce that they were closing and Monkeyhouse was losing our artistic home. I am not sure if I can articulate how disoriented I was. Compounding this overwhelming sense of mental fogginess was the fact that we do not have the language to name so many aspects of mourning and grief.

Q: How has the topic of your work developed?

A: I never expected to build a dictionary, but I have loved reference books since I was a small child hanging out in libraries with my parents. My undergraduate degree from Northwestern University is actually in Linguistics and I have found ways to weave questions about language into my dance pieces since I graduated in ’93.

Once I had a list of entries developed from my own experience, I parsed articles, memoirs, and documentaries for more. Then I discovered Writing Hard Stories: Celebrated Memoirists Who Shaped Art from Trauma by Melanie Brooks which prompted me to interview other artists who were exploring grief. Each interview expanded my sense of the landscape of loss. When I first started envisioning the dictionary, I was focused mainly on death and dying but there are so many forms of trauma – racism, sexual assault, violent crime and divorce for instance.

Q: How do we talk about the invisible- the language that is missing or the alternative language for survivors of loss and/or assault?

A: That is the central enigma of The Dictionary of Negative Space. For me, it was important to leave the ideas unnamed to illustrate how challenging it is to communicate without names. Once people read the online version and realized that those spaces were the whole point, they began to really comprehend how much I had been struggling to communicate since 2012.

For me, one of the most hopeful things about the project is the way that people start looking for negative space after going through the dictionary. I think if we can spark an interest in this missing language, then people will start developing names. If we can come up with words like smilf, Manhattanhenge and hangry, it’s time we came up with a name for the fear of forgetting the sound of a loved one’s voice, a parent who outlives a child and the last place you saw someone alive.

Q: How is your participation in the I-ARE program important to your personal and/or artistic development at this time?

A: Losing my parents and Monkeyhouse’s artistic home around the same time was a massive blow to my creative confidence. When Peter DiMuro (The Dance Complex’s Executive Artistic Director) and Rachel Roccoberton (The Dance Complex’s Creative Programs Manager) called to offer me this residency, tears silently meandered down my cheeks. Their faith in my quirky idea coupled with a regular space to build work was so generous and welcoming. It has helped me to reconnect to the larger dance community again.

On a very personal level, The Dance Complex’s Studio One (The Julie Ince Thompson Theater) is the last place that I ever attended a dance concert with my father. Two weeks before he died, we watched Monkeyhouse in Luminarium’s first 24-hour Choreofest. It was a quintessentially perfect day with my dad, who loved experimental ideas and we sat next to two of my students from Impulse Dance Center. I cherish studio one all the more because of the memory of that day and how it lives in that space.

A funny moment happened when I was watching the New England Presenters Concert where local dancer and choreographer, Michael Figueroa, was performing. Kind of out of nowhere, he said, “your father just walked in and he sat down right there” as he pointed exactly at the seat my father had sat in at the 2012 Choreofest. It was this weird coincidence, but it made me aware of how much of my past history The Dance Complex holds.

Q: Can you share more about your experience as an I-ARE Artist so far?

A: One of the best benefits of being an I-ARE resident is just being in The Dance Complex more, hearing other rehearsals, bumping into people in the hallways and taking workshops.

One of the things that’s interesting about The Complex is the number of people in the building at all times which makes me really aware of how many stories are within the community at The Dance Complex – it’s a resource that goes beyond being in the studio with people.

I wasn’t expecting to run into so many Work Studies and community members who have talked about stories of loss they have endured. It’s really fascinating that the human resources of the building itself are within this interesting physical space that holds all of these years of having been there: all these different generations of dance movement within the building and how different people, from having studied with someone, hold that person’s dance technique within them. This has been unique to my previous experiences of working with people in dance space that is less alive, which has been a real surprise.

DeAnna and I (DeAnna Pellecchia, I-ARE Artist alongside Krolak this year at The Dance Complex) both agree that as soon as we sat down and talked about what we were going to be working on, The Dance Complex seemed to choose projects for this year’s I-ARE Residency that would leverage what happens within the residency to bring as many voices to the table in the two night’s performances as possible. By bringing in two people that are working collaboratively with their companies it’s bringing a number of voices into each of these subject and I think that’s a really remarkable thing for The Dance Complex to have done.

The value of the program is not just the space given or the concert The Dance Complex is able to produce, but the support of the building as well. Whoever is funding the I-ARE program deserves a standing ovation.

To purchase tickets for Karen Krolak’s I-ARE performance, click HERE.

To learn more about The Dance Complex’s I-ARE Program, click HERE.